How is Single Malt (Scotch) Whisky made?

I’m just returning from a 3-week trip to Scotland where my wife and I had planned to do a lot of hiking, but the weather was unexpectedly poor so we learned a lot about single malt whisky instead. While the process is still fresh in my mind, I thought that I’d share the whisky making process using photos from my trip to illustrate the various steps.

The iconic architectural feature of almost every Scotch Whisky distillery is the pagoda-style roof for drying the barley.

What is Single Malt Scotch Whisky?

Scotch whisky must be made in Scotland using only Barley, Water and Yeast, and it must be aged in oak barrels for at least 3 years. To be called a “Single Malt” Scotch whisky, the liquor needs to come from just one distillery. Distilleries are allowed to mix barrels of different ages, or different types of barrels (ex: Sherry casks / American Bourbon casks). Traditionally, the bottle will have a specific age (ex: Ardbeg 10 Years Old), but some distilleries are blending different ages and selling products with a name instead of a specific age (ex: Ardbeg Uigeadail).

When whiskies from more than one distillery are blended together, the result is a blended whisky like Johnny Walker or Chivas Regal. This is similar to how some of the best relatively inexpensive wines are often a blend of multiple varieties.

How Single Malt Whisky is made in Scotland

What follows is a summary of the whisky making process. along with a collage of photos from many different distilleries across the main whisky regions of Scotland including Speyside (lighter whiskies), Northern Islands of Skye and Orkney (lightly peated), and Islay (heavily peated).

Before we get started, here is a quick summary of the main steps:

- Grow and harvest barley.

- Malting the grain produces enzymes required to extract sugars

- Drying the grain

- Milling the grain cracks it open

- Mashing the grain allows enzymes to extract sugar

- Fermenting the sugary water to create alcohol. ~8%

- Distilling the liquid twice: to reach ~28%, then ~65%.

- Aging the spirits in Oak casks to improve flavor.

- Bottling the aged whisky for sale

It’s worth noting that the first 6 steps are identical to the process of brewing beer, although beer requires the addition of Hops which act as a preservative and give beer a slightly bitter flavor.

1. Grow and Harvest Barley

Most distilleries try to buy grain from Scotland, but this is not a firm requirement for a Scotch Whisky. A few distilleries are taking this one step further and trying to buy grain from right next door to their distillery. For example, Kilchoman 100% Islay, or Bruichladdich Islay Barley. (They might even tell you which farm grew the barley!)

2. Malting

Grain which has been harvested is dry, but it isn’t yet ready to make into whisky. As we all know, grain is filled with carbohydrates, which are chains of simple sugars. Yeast can convert sugar into alcohol, but it can’t break down the carbohydrate chains. As such, the grain will be malted, then mashed to convert the carbohydrates into sugars.

A large tank is used to soak the barley. This one is at Kilchoman, and is much smaller than most distilleries would use.

Malting is a strange process. If you soak the harvested grain in water for about a day, it will begin to sprout. (Barley is a seed after all…) After a day, the wet grains are spread out on the floor of a large room to keep growing and slowly dry out. If left alone, the sprouts would tangle into a large clump, so the grains are raked every 8 hours to keep them loose and to ensure that they dry evenly. Even after a couple days, the grain is still damp, but the sprouting process has slowed down. This process produces the naturally occurring enzymes which will convert the carbohydrates into sugar later.

The grain is spread out on the floor to dry. (Highland Park still malts some of their barley the old fashioned way.)

Only a couple distilleries still malt and kiln-dry their own barley, as it is an labor-intensive process. The only two distilleries where we took tours that still malt some of their grain are Kilchoman on Islay, and Highland Park on Orkney, and even they only malt a small proportion of their grain. The rest is malted in huge malting factories where the process is highly automated using massive drums to turn the barley as it dries. (Sadly, they don’t offer tours.)

3. Drying

The grain needs to be completely dried out before it can be used to make beer or whisky. This is done in a large kiln, where the grain is placed on a fine wire mesh above a heat source until it is completely dry. Any heat source will do, so each region has a tradition of drying their grains using the cheapest source of fuel. In the mainland, coal would be used, which burns very cleanly and imparts very little flavor to the grain.

The damp barley is dried using a coal or peat-fired kiln. Highland Park (left) and Kilchoman (center) still dry some of their grain on premises, whereas Edradour (right) has a nice clean kiln since they don't use it anymore.

On the islands, there is neither wood nor coal, so they would use readily-available peat to dry the grains. Peat burns with a dark pungent smoke, which adds a smoky flavor to the grain and the whisky. This is how Islay whiskies get their peaty/smoky flavor. In modern times, the amount of smoke imparted on the grain is carefully measured for consistency in PPM (Parts Per Million). Laphroaig uses barley with 40ppm, Ardbeg uses 54ppm, and Bruichladdich Octomore (The peatiest whisky of them all) currently uses malt with 169ppm.

People still harvest peat in really rural areas to heat their homes. (This was on the isle of Lewis) The commercial distilleries still do it the same way.

4. Milling

Even though the grain has already been sprouted, the barley is still mostly sealed up. The milling process breaks the husk and allows access to the carbohydrate rich inside. Most distilleries use the same Porteus Milling machines; many are over 100 years old and still in use. (They are so reliable that nobody needed to replace them, so the company who made them went out of business.)

Bruichladdish distillery uses an even older Boby mill, although the principle is the same. The grain is cracked falling through the first set of rollers, and crushed just right in the second set of rollers.

The goal of the process is to break the grain down into a grist containing 20% husk, 70% grit and 10% flour which is the ideal ratio for mashing.

5. Mashing

Mashing is the process where enzymes break the carbohydrates in the grain down into sugar. The enzymes are naturally occurring in the malted grain, so all you need to do is soak the grain in water that’s the right temperature, and the enzymes will do all the hard work. The enzymes are most active around 68°C (155°F), but for the most complete extraction of sugars, multiple temperatures are used.

First, they add water at 65°C to allow the process to begin. After an hour, that liquid is drained and replaced by water at 70°C. That water soaks and is drained off and combined with the water from the first soak. (A third batch of water at 75°C is added to capture the remaining sugars, but this water is saved off separately and added to the beginning of the next batch as it has too little sugar to add to the wash.)

A really large covered Mash Tun at Glenfiddich distillery.

This sugary water is called “wash” and must be cooled before fermentation can begin because the yeast will die if it gets that hot. Most distilleries use a counter-flow cooling system, where cold water goes through pipes in one direction, cooling the wash which is passing in the opposite direction. This heats the water for the next mash and cools the wash so they can add the yeast.

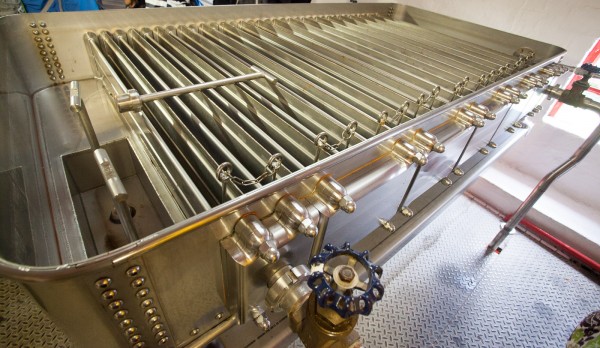

Most distilleries now use a counterflow system to cool the wort as it is more efficient, but Edradour still uses this older system which is like a radiator filled with beer soaked in a tank full of cool water.

The spent grain which is left over from this process is dried and sent to cattle farmers. Apparently the cow’s love it, although the folks at Bruichladdich told a funny story that they tried to feed the cows the spent grain from making their highly-peated “Octomore” whisky, but they took one sniff and walked away. (If you don’t like heavily peated whisky, know that your are in good company!)

6. Fermenting

The cooled “wash” goes into a huge container called a “washback” where yeast is added and the fermentation process begins. Most distilleries add a huge quantity of a very active yeast, which is able to achieve 8% to 9% alcohol in just 3-5 days. The wash doesn’t taste very good, as it lacks hops or carbonation, and is still quite warm. (The difference in flavor of an Islay peated wash and a Speyside unpeated wash is very apparent.)

A big distillery like Glenfiddich has a lot of Washbacks, while smaller distilleries might have only a couple.

This process is very similar to brewing beer, although most yeasts used for brewing beer take more than a week to ferment, and most beers are only 4-6% alcohol due to less sugar in the water.

7. Distilling

Distillation is the process which increases the alcohol level from about 9% to 65% or more. This takes place in a “still” which is a tall copper vessel where the lower-alcohol liquids go in the bottom and are heated to just below boiling. Since alcohol boils at a lower temperature than water, the alcohol vapor rises more easily than water does. Thus, the alcohol vapors rise to the top of the still, where it condenses as it moves down the neck into copper coils which are cooled with cold water.

The Wash Still (right) and Spirit Still (left) at Edradour distillery clearly show the difference in size which is common of a two-still distilling system.

Two stills are required to reach the alcohol level required to make whisky. First, the “Wash Still”, which turns the 9% alcohol “wash” into a ~25% “Low Wine”. Next, the “Low Wine Still” raises it again to about 65% Alcohol.

The alcoholic vapors are cooled to turn them back into a liquid. Most relatively modern distilleries use a closed bath, but Edradour still uses an open tank which you can see out back.

There is an important step associated with the Low Wine still to ensure best quality spirits. When the liquid in the still is heated for the first time, the very first vapors to separate from the water are of the highest ABV (around 75%), and contain a lot of unpleasant flavors. This is called the “Foreshots” or simply the head, and are set aside as they aren’t tasty. (The foreshots run for about 10 minutes.) When ABV comes down to about 70%, we have reached the “heart” of the run, where quality spirit is collected until it drops too low. Anything less than 60% is called the “feints” or simply the tail. The feints are combined with the foreshots, and added to the next batch of low wines for the next run of the low wine still.

The Spirit Safe lets the distiller measure the alcohol level without touching the liquor (or taking free samples.) This was at Ardbeg.

The resulting spirit is about 67% ABV, clear and has a pungent grassy and alcoholic flavor which you would describe as “young”. For consistency reasons, the spirit will be watered down to 65% ABV before it is placed in a barrel.

8. Aging

Scotch Whisky must be aged for a minimum of 3 years in an Oak cask, but most Single Malt whiskies are aged much longer. Barrel aging changes the flavor of the whisky and gives it a tan or reddish color. About 2% of the liquid is lost to aging every year. This loss is called the “angel’s share”, and distilelries liek to say that the angels are very happy in Scotland. Since Alcohol is lighter than water, it evaporates more quickly, so the whisky becomes a lower % alcohol over time.

Whisky must be aged for a long time to take on a dark color and rich flavor. Edradour is owned by Signatory Vintage Scotch Whisky, who buys casks from other distilleries and allows them to age shorter or longer than the standard vintage, and sells it unblended and cask strength. As such, their cellar is filled with casks from nearly every distillery.

Distilleries can use any oak cask, but most use American Oak casks from the Bourbon industry for the majority of their scotch whisky. Why Bourbon casks? Because American laws state that Bourbon can only be aged in a brand new cask, so Scotch distilleries can buy these casks which have only been used once for about 50$! Traditionally, Scotch was aged in used Sherry casks, but these have become extremely expensive in recent years as Scotch production has increased and the demand for Sherry has tanked. This is why Distilleries are looking for new ways to impart sweet / fruity tones to their whisky such as Port or Wine barrels. (Sherry casks cost about 500$, although they are about twice as large as bourbon casks.)

Distilleries decide when each barrel has aged long enough, and how they want to sell the whisky. Most relatively young whiskies are aged in 100% American Oak barrels, so they will simply mix all the barrels of the same age in a big stainless steel container where the subtle differences due to the age or flavor of each barrel will be evened out. They may give the whisky a period of time for the flavors to settle, which is called “marrying”.

Other whiskies, especially those which are 15 years or older, use a mix of American Bourbon casks and Spanish Sherry casks. In this case, a percentage of the whisky was aged the full 15 years in American oak, and the rest was aged the full 15 years in Sherry casks. The appropriate percentage of each are poured into the marrying tank, given time for the flavors to meld before bottling.

Some specialty whiskies are actually aged more than once. This is common of the “Distillers editions” of common whiskies which are generally aged for the same duration as their flagship product in American oak, then “finished” in a Sherry cask or even a first fill wine cask for 6-12 months to impart new fruity flavors.

9. Bottling

These days, most distilleries send their whisky in a huge stainless steel tanker to a bottling factory. The most common size is a 70cL bottle, but some distilleries make smaller 5cL or 20cL bottles for gifts, 50cL for expensive specialty releases, and 1L bottles are commonly sold at Duty Free shops.

Kilchoman is one of the few distilleries which still does it’s own bottling. This machine automates the filling, capping and labeling of their normal-sized bottles, but they still need to be loaded into the machine and packed into boxes manually.

A few companies still do their bottling on site. This can range from a highly automated process to a very manual process. We got to talk to the guys doing the bottling at Kilchoman, and they showed us how much of a pain it is to fill their 5cL novelty bottles. They can fill only 3 bottles at a time, and need to attach the caps and the labels by hand!

Tasting whisky in Scotland

Most distilleries offer a tour for 6£ or less, which includes at least one tasting of their flagship whisky. Many even give you a free glass that you can take home and use when enjoying your favorite single malts, we took home 13 free glasses! (All of the distilleries owned by Diageo offer free tours if you sign-up for their free “Discovering Distilleries” passport.)

Unfortunately, many of the larger distilleries do not allow photos on their tours (including all of them owned by Diageo; they claim that the camera flash can cause a fire). Thankfully, most of the smaller distilleries allow (and encourage) photography at every step in the process. While your favorite malt might be made by one of the big guys, I can’t stress enough how much more you will learn about the distilling process at one of the smaller distilleries which has only one wash still and one spirit still. (ex: Edradour or Kilchoman.) It’s much easier to see how the whole process works in a smaller, simpler distillery.

That said, by the end of the trip we learned that the old saying “you get what you pay for” is especially true when visiting distilleries. Most distilleries offer one or more “in-depth tour” or “premium tastings”. They start at around 12£ per person, but it turns out that most distilleries will let two people share the tastings and pay only one fee. We found that we could both have an adequate taste of each dram in one of these extended tastings. (Make reservations in advance, most premium tastings and tours are weekday only and by reservation.)

Premium tastings let you try things you can’t buy (or can’t afford to buy!) In this tasting at Oban, we enjoyed the classic 14 yr, their Distillers edition, their cask strength 21 yr (which is about 400$/bottle) and an 11yr old whisky which is not for sale.

Also be on the lookout for distilleries which offer more than just a tour. We loved that Ardbeg has an excellent cafe on premise, so instead of just taking a tour, we had a wonderful lunch while trying three of their expressions.

Lagavulin offers an excellent “pre-dinner tasting” which pairs four expressions of their whisky with food for 15£.

Lastly, don’t be ashamed to take notes as you taste each whisky. It forces you to pay attention to what you are tasting, and it gives you something to refer back to at the end of your trip to compare what you tried more accurately.

TOM ALPHIN builds

TOM ALPHIN builds

Great article! I’m a big single malt fan and have visited a few distilleries myself. They smell great, don’t they!

My favourites would be Talker and Highland Park.

I’ve just done a similar tour in the Niagara region of Canada: visiting vineyards and sampling icewine which is absolutely stunning…

Huw@brickset

@Huw, I agree, Talisker and Highland Park both offer a nice balance of Peaty, Oakey and other rich whisky flavours. Laphroaig and the other Islay malts are also fun, but a bit excessive.

Glad you find it to be an interesting read – we certainly enjoyed visiting so many places!